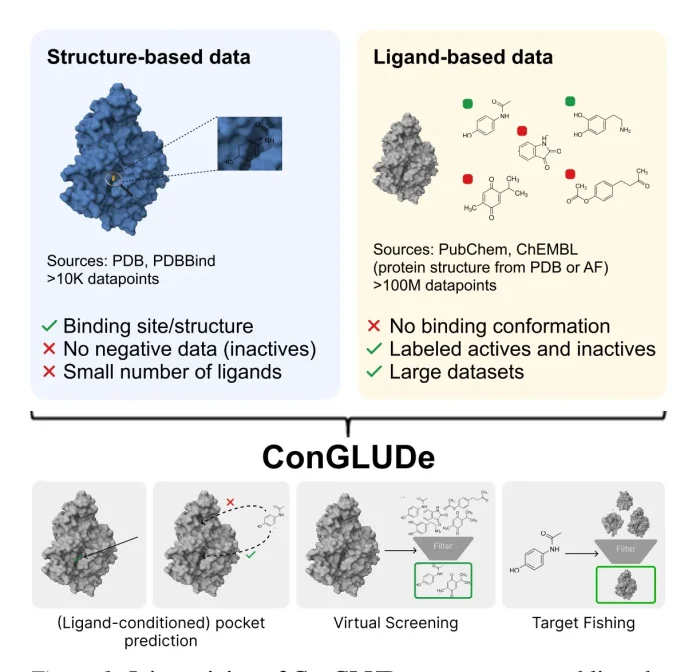

Researchers from Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria, and Merck HealthCare, Germany, developed ConGLUDe (Contrastive Geometric Learning for Unified Computational Drug Design), an AI-based model for drug discovery. The model combines structure-based and ligand-based drug designs into one system instead of treating them separately. It can predict protein-ligand interactions, find binding pockets, and perform virtual screening even when pocket information is unknown, making it a general-purpose foundation model for drug discovery.

Traditional Approaches in Drug Design: SBDD vs. LBDD

Traditionally, in bioinformatics for drug design, we opt for structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD). In SBDD, data is obtained from experimentally determined protein-ligand complexes (e.g., NMR spectroscopy) from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB). And we use methods like docking, molecular dynamics, or free energy perturbation. We also have AI for protein-ligand complex prediction, making it more accurate and detailed, but it also makes it expensive, hard to scale, and slow.

LBDD is based on ligand activity directly from the experimental assay outcome instead of ligand binding confirmation within the protein target and uses sources such as PubChem and ChEMBL. With ML-based LBDD, it’s possible to work with limited protein data, but even with being fast and scalable, it does not give binding site or pocket details. Contrastive learning models do exist, but the one trained on structure-based data can only be used on proteins whose pocket is predefined, and the one trained on ligand-based data cannot make predictions about specific binding pockets.

Introduction to ConGLUDe

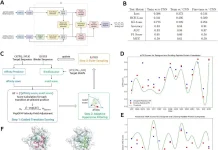

ConGLUDe is a model that unifies structure and ligand-based training. The model has a protein encoder and is based on a modified VN-EGNN architecture. It helps to understand the structure of protein as well as the possible binding sites, and the molecule encoder maps ligand into a vector to align with protein/pocket representation, while for contrastive loss function, it integrates structure and ligand-based learning, where it learns to detect and characterize binding sites and pair them with their ligand and also leverages large-scale bioactivity measurements, respectively.

Architecture Modifications in ConGLUDe

In the protein encoder, they introduced a virtual node P; this node gives the aggregated information of the entire protein, and in addition to 3 geometric message passing steps of VN-EGNN, they added two non-geometric steps: from residue nodes to the protein nodes and from protein nodes to residue nodes. This enables the model to look at the whole protein at once to improve binding site prediction.

The ligand encoder uses molecular fingerprints combined with MLPs. The Multilayer perceptron (MLP) gives each molecule (ligand) a joint 2D embedding, which is then split into a protein-matching representation and a pocket-matching representation. This helps encode large batches of ligands and makes virtual screening across large compound libraries easy.

Model Training and Result Analysis

For structure-based data training, the model was trained on geometry, which describes the binding pocket, and constructive loss gives the correct protein-pocket-ligand pair. This was done by using a 3-way InfoNCE (Noise-Contrastive Estimation loss. First, the protein and pocket embeddings together were matched with the correct ligand to teach the model which ligand belongs to a specific protein pocket pair. Second, the ligand was matched with the correct protein, teaching target recognition. Third, the ligand was matched with the correct binding pocket, teaching binding site specificity.

For ligand-based data, only activity levels (active/inactive) were available, and there was no information about binding pocket locations. Samples were taken in a 1:3 ratio to balance the data, and then the model compresses protein embedding with ligand embedding using cosine similarities. If the ligand is active, the similarity will be high, and if the ligand is inactive, the similarity will be low. This is known as sigmoid contrastive loss.

For virtual screening, ConCLUDe was compared with DUD-E (pocket-dependent models) and LIT-PCBA (pocket-agnostic models), and hybrid methods combining DrugCLIP with pocket predictors (P2Rank/VN-EGNN), and metrics like AUROC, BEDROC, and Enrichment Factor (EF 1%) were used. It was observed that DUD-E performed better than any other approach, including ConCLUDe. It performed better than LIT-PCBA and DrugCLIP with pocket predictors. For target fishing, it outperformed DrugCLIP (P2Rank/VN-EGNN), SPRINT, and DiffDock with significant value differences.

Metrics like DCC (distance from predicted pocket center to ground-truth pocket center) and DCA (distance from predicted pocket center to the closest atom of the corresponding ligand) were used for binding sites and ligand condition pocket selection. For binding sites, it performed closer to VN-EGNN, highlighting that architecture modifications and adaptations to support additional tasks do not interfere with its ability to perform well on pocket predictions. Further, for ligand condition pocket selection, ConCLUDe ranks protein pockets based on how they are likely to bind to a specific ligand, unlike other approaches that ignore ligands. ConCLUDe outperformed other approaches, especially on PDBbind; it is also much faster than others, as it scores pockets and ligands independently.

Limitation

ConGLUDe performs well for proteins with known 3D structures but may not perform well on predicted or unusual proteins. It only supports assays with a single non-protein target and cannot handle phenotypic or target-agnostic assays. It finds ligand-specific pockets fast but does not create docked ligand structures, though predicted pockets can still be used as a quick starting point for standard docking.

Conclusion

Throughout the study, ConGLUDe achieved top performance on virtual screening, target fishing, binding site prediction, and ligand condition pocket selection, while being competitive. In the future, it could integrate generating models for ligand and design and predict additional properties like binding affinity or ADMET profiles, moving towards general-purpose drug discovery models.

Article Source: Reference Paper | Code Availability: GitHub

Disclaimer:

The research discussed in this article was conducted and published by the authors of the referenced paper. CBIRT has no involvement in the research itself. This article is intended solely to raise awareness about recent developments and does not claim authorship or endorsement of the research.

Important Note: arXiv releases preprints that have not yet undergone peer review. As a result, it is important to note that these papers should not be considered conclusive evidence, nor should they be used to direct clinical practice or influence health-related behavior. It is also important to understand that the information presented in these papers is not yet considered established or confirmed.

Follow Us!

Learn More:

Jainab Shaikh is a postgraduate in Biotechnology with a strong interest in understanding how research translates into real-world innovation. Her areas of focus include biosensors, bioinformatics, and sustainable biotechnological applications. She is passionate about exploring recent scientific advancements and communicating them through clear, engaging, and accessible content. Her work particularly emphasizes research-driven narratives in healthcare, biotechnology, skincare science, and emerging life science innovations.